JENA, Germany, October 2019: An international team of archaeologists has found a collection of microliths — small, retouched, often-backed stone tools — at the cave site of Fa-Hien Lena in the tropical evergreen lowland Wet Zone rainforests of Sri Lanka. Some of these microliths are 45,000 years old and represent the earliest evidence of such advanced technology in South Asia.

“We undertook detailed measurements of stone tools and reconstructed their production patterns at the site of Fa-Hien Lena Cave, the site with the earliest evidence for human occupation in Sri Lanka,” said Dr. Oshan Wedage, award-winning archaeologist and researcher at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany.

“We found clear evidence for the production of miniaturized stone tools or microliths at Fa-Hien Lena, dating to the earliest period of human occupation,” Sci-News.com quoted Dr. Wedage as saying in a study published earlier this month in the open-access journal PLOS ONE. Dr. Wedage is a recipient of the President’s Awards, one of the most prestigious scientific awards in Sri Lanka, that are bestowed on Sri Lankan scientists for contributing world leading pieces of research.

The new study states that the island of Sri Lanka, at the southern tip of South Asia, has emerged as a particularly important area for the investigation of prehistoric hunter-gatherer adaptations and technological strategies used in tropical rainforest ecosystems. Caves and rockshelters excavated in the modern Wet Zone rainforest of Sri Lanka since the 1950s have yielded long stratigraphic sequences, with well-preserved organic plant and animal remains in Late Pleistocene and Holocene contexts. The earliest human fossils of South Asia are found in the Sri Lankan caves and rockshelters.

Fa-Hien Lena cave, one of the largest caves in Sri Lanka, and the site of the latest discovery, is situated in Yatagampitiya village, near the Bulathsinhala Divisional Secretariat Division in the Kalutara District at approximately 130 meters above mean sea level. It is a shallow rockshelter containing prehistoric habitation, situated next to a large domed cave.

Microliths are considered to be the product of composite weapons produced by cultures with advanced strategies for hunting and thriving in challenging environments. Such tools are known from Paleolithic sites in Europe, but this is the oldest microlith assemblage in South Asia and the oldest known from a rainforest environment. In the past, tropical rainforests have been thought of as a barrier to early human dispersal, being difficult to inhabit and to traverse compared to the environments of Europe and Africa. This view has been overturned by recent discoveries of rainforest cultures in South Asia dating as early as 45,000 years ago, but uncertainty still exists about what kind of technology allowed early cultures to survive in these habitats.

However, the discovery of these tools, which are believed to have been weapons to kill animals hiding in trees, suggests humanity spread more diversely than was thought. The tools—along with the formation of complex social structures—may have been key in letting humans adapt to life in the rainforest and nearly every habitat beyond.

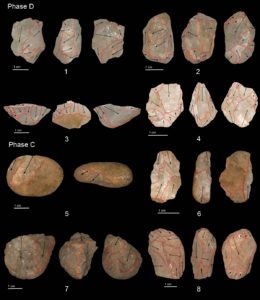

As part of their research, Dr. Wedage and colleagues collected 9,216 artifacts, including 1,730 artifacts older than 34,000 years. The dominant raw material used at Fa-Hien Lena is quartz. River pebbles with smooth surfaces were most likely gathered from the stream located 200 m from the site.

“These tools were likely part of composite projectile technology used to hunt and capture tree-dwelling prey, though more research will be needed to confirm their exact functions,” said the authors of the study,

The similarity of Fa-Hien Lena technology to that of local cultures as recent as 4,000 years old reflects a long-term stability in rainforest technology in the region.

“The lithic technology of Fa-Hien Lena changed little over the long span of human occupation (from 48,000-45,000 years ago to 4,000 years ago) indicating a successful, stable technological adaptation to the tropics,” the scientists said.

“Microliths were clearly a key part of the flexible human ‘toolkit’ that enabled our species to respond — and mediate — dynamic cultural, demographic, and environmental situations as it expanded over nearly all of the Earth’s continents during the Late Pleistocene, in a range currently not evident among other hominin populations,” they concluded.