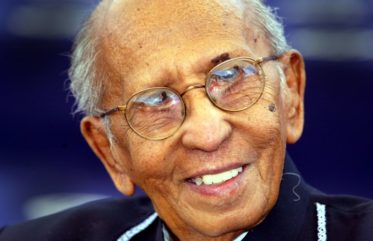

The doyen of Sinhala cinema Dr. Lester James Peries was laid to rest amidst a large and distinguished gathering at the Independence Square in Colombo on 2 May. Dr. Peries, who was born on 5 April, 1919, passed away on 29 April at the age of 99.

The funeral was conducted with state patronage and President Maithripala Sirisena, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe and former President Mahinda Rajapaksa were among those who gathered to bid farewell to the renowned film maker. The government also declared the day of his funeral as a Day of National Mourning as a mark of respect.

In a special obituary, the prestigious New York Times described him as a visionary filmaker, whose films about the dynamics of family life in Sri Lanka brought world recognition to that island nation’s movie industry.

Following is the article published in the New York Times:

Starting with “Rekava” (“The Line of Destiny”) in 1956, Mr. Peries’s films offered a significant shift from formulaic Indian-influenced dance and fantasy movies that had been standard fare in Sri Lanka, which was known as Ceylon at the time. He wanted his pictures to accurately reflect the lives of the Sinhalese people, who constitute most of the country’s population.

He described his movies as the “cinema of contemplation,” in which the cameras “eavesdrop on life” to expose his characters’ psychology.

“Seemingly, on the surface, nothing happens,” Mr. Peries (pronounced PEER-ease) told The New York Times in 1970, “and yet by the quietest of means, scene by scene, incident by incident, one hopes that the interior drama is revealed.”

Making Sinhalese films, he told The Daily News, a Sri Lankan newspaper, in 2015, was a way to honor the cultural background of his grandmother, who only spoke Sinhalese. Growing up in an Anglicized Roman Catholic family, he said, had “distanced us from our roots” and “sped up a process of westernization.”

“Some of us became snobs,” he said.

He and his brother, Ivan, a painter, wanted to reclaim their roots.

“Rekava” is set in a rural village where a boy is thought to have magical powers after he apparently heals a girl’s blindness. Describing its impact, the Sri Lankan director Asoka Handagama told The Hindu, an Indian newspaper: “They say that Dostoyevsky once said, ‘We all come out of Gogol’s “Overcoat.” ’ The same way, we all came out of Peries’s ‘Rekava.’ ”

“Rekava” was the first Sri Lankan film nominated for the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. The award went to William Wyler’s “Friendly Persuasion.”

Mr. Peries made 20 features over 50 years, including “Gamperaliya” (“Changes in the Village”) in 1963, which earned him the Golden Peacock for best film at the International Film Festival of India. In an interview for a film about his life, “The World of Peries” (2001), he described the award as a “miracle” that had liberated him from a sporadic schedule of filmmaking to a more regular one.

His recognition by the Indian film festival coincided with a blossoming friendship with Satyajit Ray, one of India’s greatest directors. Their debut films were released within a year of each other, and each is considered a critical figure in his country’s film history.

D. B. S. Jeyaraj, a Sri Lankan journalist who writes about film, wrote of Mr. Peries: “It was he who created in every sense of the term an indigenous cinema in both substance and style.”

Mr. Peries was born on April 5, 1919, in Dehiwala, a suburb of Colombo, to James and Ann Gertrude Winifred (formerly Jayasuriya) Peries. His father was a doctor who had been educated in Scotland.

When he was 11, he received an eight-millimeter film projector from his father. At 17, he dropped out of St. Peter’s College to become a journalist for Ceylonese newspapers. He moved to London in 1947 and wrote an arts column for The Times of Ceylon. While in London he also made short films, which earned him awards.

Mr. Peries returned to Sri Lanka in the early 1950s to make documentaries for the government. By 1956, he had moved on and begun to make his own feature films, along with the occasional short documentary.

The Museum of Modern Art in New York held a retrospective of Mr. Peries’s career in 1970.

“He has the purity of vision that makes us forget that his locale is exotic, his people foreign,” Donald Richie, who curated the retrospective, said at the time. “He is making films for the whole world. He is a humanist speaking through the language of film.”

One of his last films, “Wekande Walauwa” (“Mansion by the Lake”), inspired by Chekhov’s “The Cherry Orchard,” was shown at the New York Film Festival in 2003. Writing in Variety, the critic Derek Elley said that the film’s “slight artificiality is redeemed by Peries’s customary gentleness and serene humanity.”

Mr. Peries married Sumitra Gunawardena, a director who edited “Gamperaliya” and who was Sri Lanka’s ambassador to France in the 1990s. Her recently released film “Vaishnavee” is based on a story by Mr. Peries. She survives him.

One of Mr. Peries’s most acclaimed films was “Nidhanaya” (“The Treasure”), from 1972, which, a reviewer for The Los Angeles Times wrote, “shows him as a considerable director in the intensity of feeling he can convey to an audience that knows little of the society he portrays.”

The story of a man obsessed with a buried treasure, “Nidhanaya” was all but lost until a restoration was completed in 2013 by a group that included the World Cinema Project. It was subsequently screened at the Venice Film Festival, where it had been shown in 1972. Mr. Peries said at the time that he had been lobbying for decades for better film preservation in his country.

“When I first attempted to lobby for a national archive over 50 years ago, soon after I completed ‘Rekava,’ I was mocked by many,” he told The Island, a Sri Lankan newspaper. “ ‘Having done only one film, this man is trying to reach the moon!’ they said.”

He added, “I cannot fathom why there is no state action to establish one, which will preserve part of our national history.”

A year later, the government opened a film, television and sound archive with an exhibition about “Rekava.”